From Hospital Gown to Graduation Gown: Two Men Devoted to Alleviating Suffering

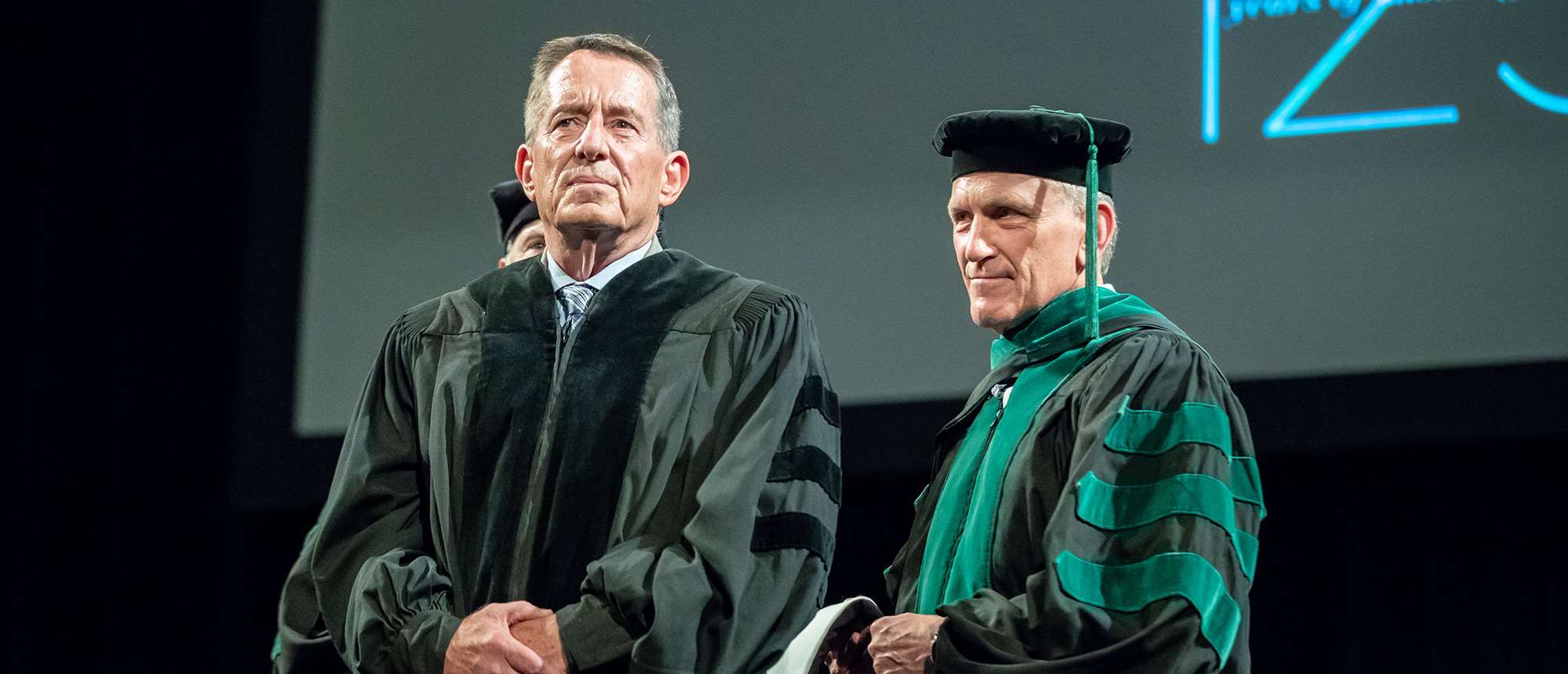

When Michael Orban first met Michael Dailey, MD, in 1979, Orban was wearing a hospital gown. When they met again last week at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) Commencement Ceremony almost 40 years later, he was wearing a graduation gown. Orban received an honorary degree from MCW, the same institution where he became the first patient diagnosed in the U.S. with the filarial disease Acanthocheilonema perstans (A. Perstans) from the bite of a tsetse fly. Dr. Dailey, whose tireless efforts to find the correct diagnosis for Orban saved his life, was there to hood Orban at the ceremony.

"When I learned I was receiving this honorary degree, I knew I wanted Dr. Dailey to be the person to hood me," Orban says. "From the first time I met him, he was enthusiastic, professional and determined. I believed in him and his abilities from the very start."

Looking for Answers

Dr. Dailey had completed his residency training through MCW and was an MCW infectious disease fellow when he first met Orban in 1979. He still remembers the day he was moonlighting at the hospital that is now Community Memorial Hospital; the head of Medical Associates Clinic requested he come take a look at a Peace Corps volunteer who had recently returned from Gabon in West Africa with an unusual rash.

"I completed a master's degree in microbiology prior to my medical training, so I had some expertise in that area. But I understood very quickly this case would take a very high level of expertise – and some luck – to diagnose," Dr. Dailey recalls. He transferred Orban to what is now Froedtert Hospital, where a team came together to work with Dr. Dailey to begin a laborious search for a diagnosis. But this was not the first time Orban had sought a diagnosis.

Orban, a Wauwatosa native, explains he had previously sought treatment from national experts, but nobody could give him the answers or treatment he needed. By the time he found himself in Dr. Dailey's care, he had already resigned himself to the fact that his disease might be fatal.

Orban, a Wauwatosa native, explains he had previously sought treatment from national experts, but nobody could give him the answers or treatment he needed. By the time he found himself in Dr. Dailey's care, he had already resigned himself to the fact that his disease might be fatal.

"Initially I had sought treatment in Gabon while I was living there, and I became very alarmed when even the local doctors trained in Western medicine as well as local medicine said they had never seen a case like this before," Orban recalls. "I was sent back to the U.S. to be examined by the leading tropical disease experts for the U.S. State Department in Washington, D.C., but even they were at a loss. After tests and biopsies, nobody could provide the answers I needed. So I was sent home to Wisconsin."

"I thought to myself, 'I have a tropical disease, and I'm going home to a winter climate where nobody will be familiar with this.' I understood I was being sent home to die."

The effects of the illness were agonizing, Orban reflects. He had golf ball-sized welts and pustules on his back that were itchy and painful. His skin began deteriorating, and large scars from his welts remain even today.

A Mission Derailed

Being forced to return to the U.S. because of his infection was especially difficult for Orban because he had originally gone to Africa seeking healing from other wounds. Orban, a Vietnam War veteran who was drafted in 1969, returned to Wisconsin after completing his service with severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), though a formal diagnosis of PTSD was unavailable for Orban at the time. (It wasn't until 1980 that the American Psychiatric Association formalized PTSD as a diagnosis, and it would take years before treatments would be better understood.) As an infantry soldier, he dreamed of attending the University of Wisconsin-Madison when he returned with his GI Bill. PTSD derailed his plans.

"I remember walking around the Capitol and up Bascom Hill in this place I had dreamed of attending surrounded by so many students, and they were all so excited and full of energy. But I was angry, isolated and hit very hard by depression," Orban recalls. "I had wanted so much to go there and thought I would be returning home to what life had been like before the war. But I couldn't focus at all and just wanted to scream at the other students who seemed so happy around me, 'If you only knew what people do to each other at war.'"

One day during a walk around campus, Orban passed a window flyer featuring the African continent and the words, "Peace Corps: The toughest job you'll ever love," and immediately signed up. Orban ultimately spent several years in Africa, where he found peace and reprieve that helped him cope with the devastation he felt from war.

"Africa saved me; it's that simple," he says. "Among those cultures, I reconnected with the majesty, beauty and wildlife of Africa, and it restored me from the bitterness I had. The village people, the pygmies and the jungles of remote Africa, meeting a personal hero, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize Dr. Albert Schweitzer, and visiting his hospital in Gabon all helped me reconnect to love and forgiveness. Dr. Schweitzer's teachings on 'Reverence for Life' had a deep impact on me. In Africa, I had a deep sense of belonging to something much bigger and more majestic than myself."

Although Orban was reluctant to leave Africa behind, his infection meant he was forced to return home for treatment.

"I was devastated at the thought I might never see Africa again," he says. But Dr. Dailey's tenacity to find a diagnosis gave Orban renewed hope.

Diagnosis Determined

When he first met the determined young fellow only a few years his senior, Orban remembers he thought to himself, "If he wants to try to find a diagnosis nobody else can, let the guy try." Although Dr. Dailey understood Orban's case had defied even the nation's leading medical experts, he was not deterred. He performed tests and biopsies that revealed Orban had a filarial infection, but because the parasite was unknown, it was risky to treat the disease.

"Different parasites require different treatments," Dr. Dailey says. "We knew he had an inflammatory condition, but we couldn't identify the filarial parasite. After much deliberation, I decided to treat him with diethylcarbamazine. His condition worsened, but that was normal during such treatment cycles. I had a biopsy sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for their review. I knew from my time studying microbiology that they were the gold standard of pathology. They were able to diagnose the organism A. Perstans, revealing that we had been treating him accurately."

Orban says he will never forget the day Dr. Dailey told him the news.

"He came running into my room at full speed with his white coat flying out behind him, and he said, 'We got it, we got it! We know what it is,'" Orban recalls. "I was so grateful, I just dropped to my hands and knees. I knew this meant I would survive and could go back to Africa."

Ultimately, Orban's lesions cleared up, and he was healed. Because his infection was the first diagnosed case in the U.S., the case was registered with the World Health Organization.

Paying it Forward

Dr. Dailey went on to practice in Atlanta and collaborate on cases for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but he says Orban's diagnosis was among the rarest illnesses he has seen throughout his career and among those he is most proud of treating.

"I look back very fondly at my time at MCW and at that case in particular," Dr. Dailey says. "The chief of medicine, Daniel McCarty, MD, and the director of the residency program, James Cerletty, MD, and my colleagues all contributed to the kind of doctor I became and how I practiced medicine. Receiving my training at MCW was the best decision I made."

Like Dr. Dailey, Orban has used his life to aid others. He went on to spend many more years serving in various African countries through the Peace Corps and then USAID projects. He ultimately returned to the U.S. and finally received information about and a diagnosis of PTSD. He checked himself into an inpatient treatment program at the Milwaukee VA Medical Center, and today he devotes his time to helping others who struggle with PTSD and hopes to bring more awareness and understanding to the condition so others don’t have to suffer alone. Orban has written a book about conquering combat PTSD, Souled Out, A Memoir of War and Inner Peace, is a keynote speaker, assists incarcerated veterans in Wisconsin, and works with the VA and MCW students on the Warrior Partnership Program. Ultimately, he hopes his work will help veterans and civilians understand, resolve, accept and take ownership of PTSD.

"My passion is helping people who have suffered," he says. Orban and Dr. Dailey have stayed in touch over the years, and Dr. Dailey says watching Orban's achievements has been rewarding.

"This honorary degree for him exemplifies the reason people get excited about treating patients," Dr. Dailey concludes. "You get to watch people who were once sick get better and go on to have successful careers, families and lives. For most doctors, that's the most rewarding thing. To see Michael [Orban], who would have been disabled or possibly not survive this illness, use his life the way he has is wonderfully satisfying. Michael Orban used his time to 'pay it forward,' as they say. I could not be more proud of him and what he has done with his life."