Precision Epidemiology and Overdose

“I’m an impatient person,” says John Mantsch, PhD, Florence Williams Professor and chair of pharmacology and toxicology at MCW. As a neuroscientist, Dr. Mantsch has been interested in how the brain works since the earliest days of his training, and his own laboratory research has focused on the effects of stress and substance abuse on brain function. More recently, he has changed the scope of some of his research from the microscopic level to examine entire communities and cities.

“I’m going to continue the basic science work because of all we need to learn there,” Dr. Mantsch adds. “Basic science requires a lot of patience, so I see the community-level research as a chance to help create a more immediate benefit.”

The problem could not be much more immediate. Deaths from drug overdose in the US rose in 22 of the last 23 years and were projected to be more than 110,000 in 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Milwaukee County, overdose deaths have grown by more than 80 percent from 2016 to 2021 with 623 deaths recorded in 2021.

“To better counter these alarming trends, we need more precise information about the issue,” Dr. Mantsch says. “We tend to think about problems at the level of the city rather than looking more closely at the many communities within a city.”

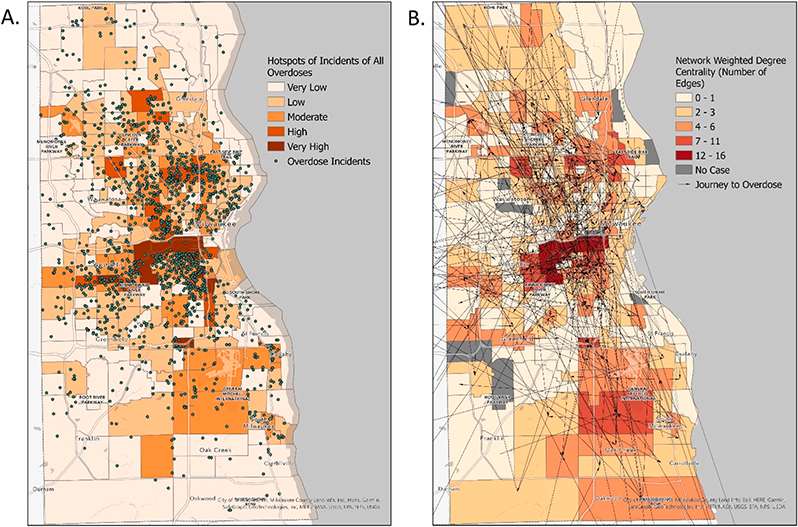

The map on the left (A) shows overdose death locations and census tract hotspots from 2017-2020. The warmer colors denote census tracts with higher numbers of overdose deaths during this timeframe.

The map on the right (B) depicts overdose journeys from 2017-2020. The warmer colors highlight census tracts with more journeys originating from or ending at a particular tract.

Dr. Mantsch partnered with a team of geographers and data scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee led by Rina Ghose, PhD, professor of geography, to look at data on overdose deaths in Milwaukee County. They looked for patterns that can help communities develop or improve prevention plans. Taking inspiration from studies by criminologists investigating the distance individuals travel before breaking the law, known as the “journey to crime,” Dr. Mantsch and the team opted to study the journey to overdose. The team developed their dataset by comparing the locations of overdose deaths with addresses of residence provided by next of kin that were recorded on death certificates from 2017 through 2020. The scientists published their findings in Drug and Alcohol Dependence in February 2023.

“We found that in nearly 27 percent of cases, individuals traveled away from their communities of residence and suffered overdose deaths in different communities, which we call geographically discordant overdose deaths,” Dr. Mantsch says. “We conducted spatial social network analysis to find patterns of where these overdoses are more likely to occur and better understand characteristics of individuals who are more likely to undertake a journey to overdose.”

The researchers developed a color-coded map highlighting census tracts that have been hotspots for geographically discordant overdose deaths from 2017-2020 with risk levels ranging from very high to very low. The team also determined which census tracts were more likely to be starting points for journeys to overdose. Most victims traveled less than 5.5 miles during the journey to overdose to one of eight census tract hotspots. Geographically discordant deaths more commonly involved fentanyl, cocaine and amphetamines than non-discordant deaths, and were more likely to be accidental.

Dr. Mantsch sees the detailed information about individuals and communities involved in journeys to overdose as part of a new approach to studying the dynamics driving health issues such as the drug overdose epidemic. He calls this shift to better understanding community- and neighborhood-level subtleties “precision epidemiology.”

“These neighborhood-level dynamics could inform more precise public health prevention plans and the availability of harm reduction resources, such as adjusting the supply of Narcan so it can be used where it is needed most,” Dr. Mantsch notes. “This is the level of detail we need to understand to accelerate our progress in addressing this epidemic.”

In addition to his academic partners at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Dr. Mantsch works with numerous others to help with the research and put the team’s findings into action, including the data surveillance and informatics team in the MCW Comprehensive Injury Center led assistant professor of epidemiology Connie Kostelac, PhD, the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner, Milwaukee County Office of Emergency Management, City of Milwaukee Health Department, Project WisHope, Social Development Commission and other neighborhood organizations.

“Data by itself is only part of the story,” Dr. Mantsch adds. “None of this is effective without the understanding of and partnership with our communities.”

Authors: Dr. Mantsch’s coauthors are Amir Forati, PhD candidate, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee department of geography; Rina Ghose, PhD, professor of geography, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Fahimeh Mohebbi, PhD candidate, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee department of computer science.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts.