Preserving Critical Language Regions During Epilepsy Surgery

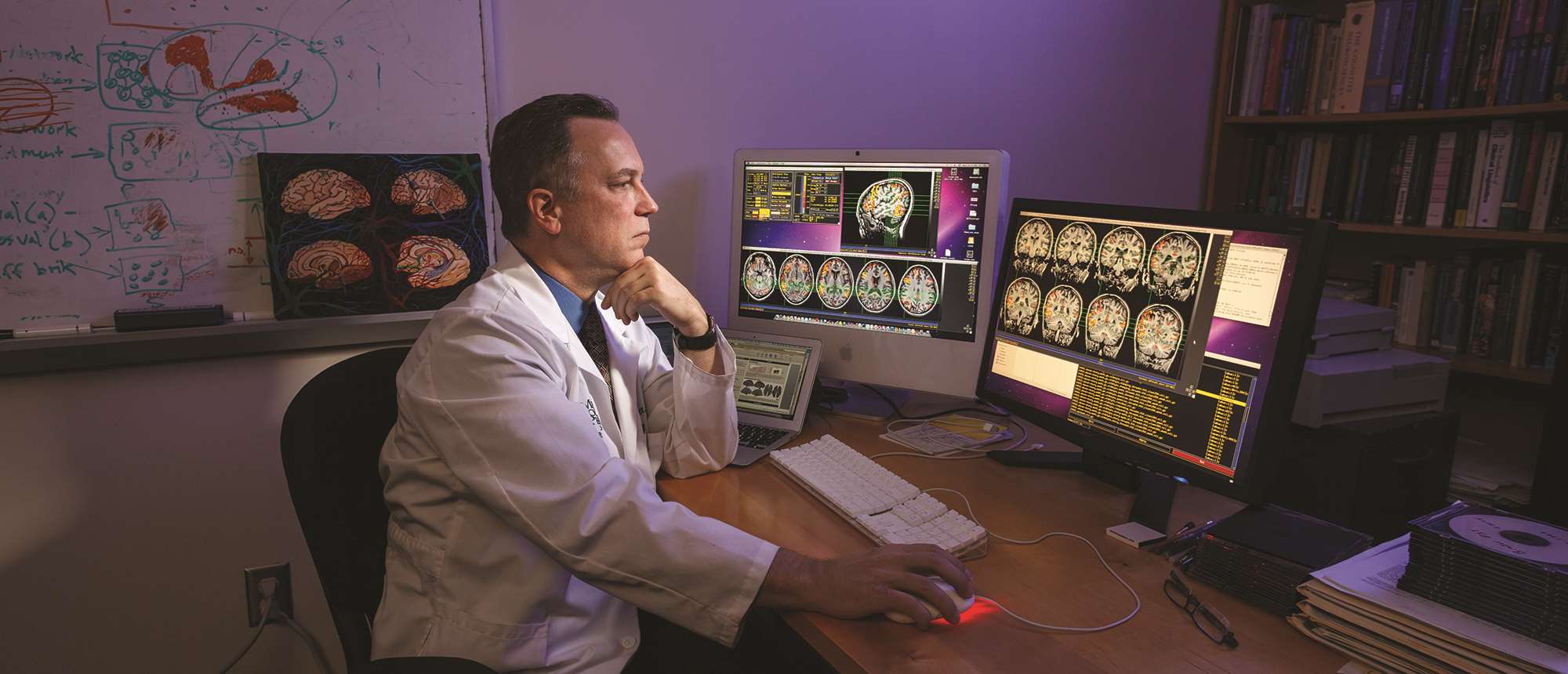

Dr. Jeffrey Binder is undertaking pioneering research on potential side effects of epilepsy surgery.

When medication can’t control the recurrent, unprovoked seizures of epilepsy patients, many turn to a surgery first developed in the 1950s that involves removing a portion of the brain where electrode mapping indicates the seizures arise – often in the temporal lobe. While this treatment can cure epilepsy some 70 percent of time, it does not come without the risk of side effects, especially if the source of the epilepsy is the left temporal lobe.

This is because most people’s language abilities come from the left side of the brain, which can be determined on an individual basis using functional MRI imaging, thanks to the pioneering work of Jeffrey Binder, MD, MCW professor and vice chair of research in the department of neurology and director of MCW’s Language Imaging Laboratory.

The potential side effect with left temporal epilepsy surgery is post-surgical decline in the ability to come up with names for objects, even with a visual cue. According to Dr. Binder, some people have no change in their naming ability after surgery while others might decline by 20-25 points on the 60-point assessment of this brain function – which neurologists complete through a test that shows 60 pictures of objects and asks patients to identify them.

Known risk factors for this decline, including location of the patient’s language functions in the brain, age and later onset of epilepsy in life, explain only about 25 percent of the variation in outcomes for patients in terms of naming ability.

“Very few hold the opinion that you shouldn’t do the surgery because it’s much more important for most people to get rid of their seizures than to preserve 100 percent of their naming ability,” notes Dr. Binder. “But at the same time, we want to limit that decline in naming ability as much as possible.”

Dr. Binder set out to see if the variation could be explained by what parts of the temporal lobe are removed during epilepsy surgery and therefore improve outcomes for patients.

“The surgery isn’t done in the same way from person to person. Not only does the suspected location of the seizures vary from patient to patient, so does the way surgeons perform the procedure and which areas of the brain they prioritize in preserving versus removing,” explains Dr. Binder.

To see the impact of this variety across both patients and surgeons, Dr. Binder set up a consortium of nine epilepsy centers and built up a database of 59 people who had had left temporal epilepsy surgery over a span of five years. Each patient took the standard naming test before and after surgery and had images taken of their brain before and after so that Dr. Binder

and his team could map the area of the brain removed. This was the first study of its kind.

“We found that the more the surgery extends back from the front part of the left temporal lobe into the middle part of the temporal lobe, the more naming decline the patient faced as a result,” he explains. The results were published in the September 2020 edition of Epilepsia.

According to Dr. Binder, the existence of a language center in that area – the underside of the temporal lobe midway along the axis from front to back – was first suggested about 30 years ago. Evidence was somewhat ignored to a large extent because that region isn’t often stimulated in brain mapping studies.

“Our study highlights the critical nature of this brain region for preserving naming abilities,” he says. “We hope the results of this study will provide enough evidence to persuade surgeons to try to preserve that area as much as possible and lower the risk of the decline in naming ability.”

– Karri Stock