Treating Cancer through Precision Medicine

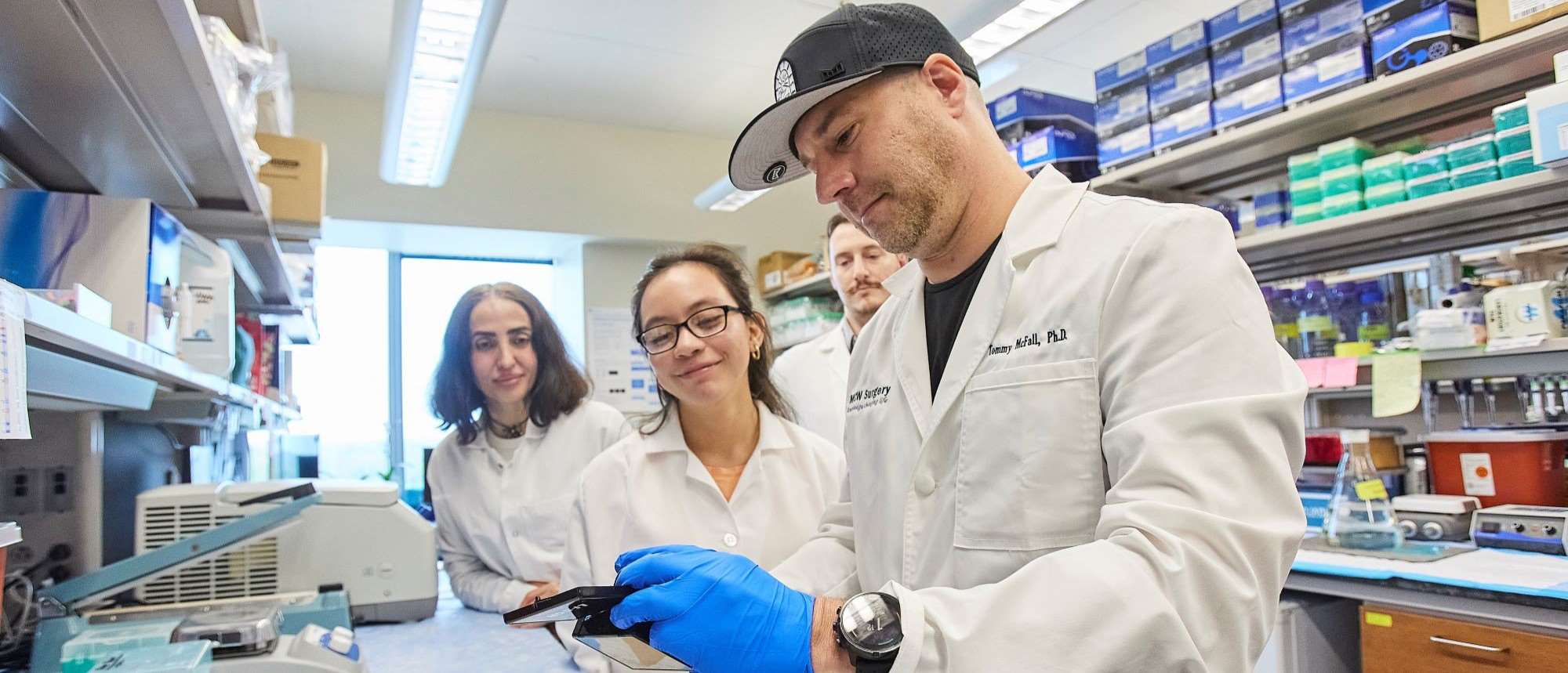

Cancer research has long been governed by established theories – rules about which mutations respond to which drugs and which don’t. Tommy McFall, PhD, an assistant professor of biochemistry at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), challenges those assumptions, opening doors for more personalized cancer treatments and bringing hope to patients who had few options before.

Dr. McFall’s journey into cancer research began with a master’s thesis on glioblastoma, a highly aggressive brain tumor. He pivoted to studying breast cancer for his doctoral thesis, focusing on hormone receptors and how sex hormones influence tumor progression.

His quest for a deeper understanding of the disease led him to the prestigious Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Surrounded by physicists and engineers, Dr. McFall began to approach cancer research differently.

Rather than solely focusing on biological mechanisms, he integrated mathematical models to understand complex clinical phenomena – like why some patients respond unexpectedly well to specific drugs.

One of his first breakthroughs came while studying Cetuximab, a drug used for colorectal cancer. Traditional guidelines dictated that patients with specific RAS mutations would not respond to the treatment.

When Dr. McFall examined clinical data, he found patients with the mutation who did, in fact, respond. His work revealed that some RAS mutations activate wild-type RAS proteins, which are still susceptible to drug targeting.

"We found that if you inhibit the wild-type version of RAS, it’s enough to stop the tumor from growing," Dr. McFall says. "We didn’t need to develop a new drug – we just needed to look at the problem differently."

Approximately 30,000 colorectal cancer patients annually were excluded from receiving Cetuximab based on conventional guidelines. Dr. McFall’s research showed that many of these patients could benefit from the drug, marking a profound shift in how treatment could be approached.

Personalized Medicine for Pancreatic Cancer

Dr. McFall’s research extends beyond colorectal cancer. At MCW, he participates in the PROTECT-PANC trial, which aims to examine the efficacy and safety of personalized matched therapies in pancreatic cancer patients at high risk of disease recurrence post-surgery.

Instead of the conventional high-dose chemotherapy with one targeted therapy, the trial employs multiple drugs at significantly reduced doses. The aim is to attack various cancer pathways simultaneously with less toxicity.

"It’s about precision medicine. If you have four mutations, we target all four, but at lower doses to reduce toxicity – and patients are doing better,” Dr. McFall notes.

One patient with a rare G12R KRAS mutation – a typically lethal form of pancreatic cancer – responded so well to the MEK inhibitor trametinib that their tumor became undetectable within months. Given that the standard survival rate for this condition is about two months, the patient’s nearly two-year survival was remarkable.

An Eye Toward Exceptional Responders

Currently, Dr. McFall is building a research program that combines his expertise in systems biology, MAPK signaling – another crucial cell signaling pathway involved in cancer – and nuclear receptor signaling.

He seeks to unravel the mysteries behind "exceptional responders" – cancer patients who experience unexpectedly positive outcomes from specific treatments. By investigating the molecular profiles of these extraordinary cases, Dr. McFall hopes to identify the underlying mechanisms that contribute to their favorable responses.

Rather than dismissing rare positive responses as anomalies, Dr. McFall sees them as windows into new treatment possibilities. This knowledge could be invaluable in developing new predictive biomarkers, allowing clinicians to better select the most effective therapies for individual patients.

Dr. Fall’s work ensures that each patient’s unique genetic profile is considered, aiming for precision medicine that goes beyond one-size-fits-all protocols. This approach makes him optimistic about the future of cancer care.

"We’re not curing cancer yet," he acknowledges, "but we’re moving the needle – and that’s how you know you’re on the right path."