Preventing Blindness by Untangling the Genetic Network of Vision Neurons

The neural cells responsible for vision develop early – a mere 28 hours after fertilization for zebrafish, 33-35 days after for humans.

Called retinal ganglion cells, they connect the eyes to the brain as the sole output neuron of the retina. When anything goes wrong with this neuron – whether in early development or later in life through diseases like glaucoma – it can cause blindness.

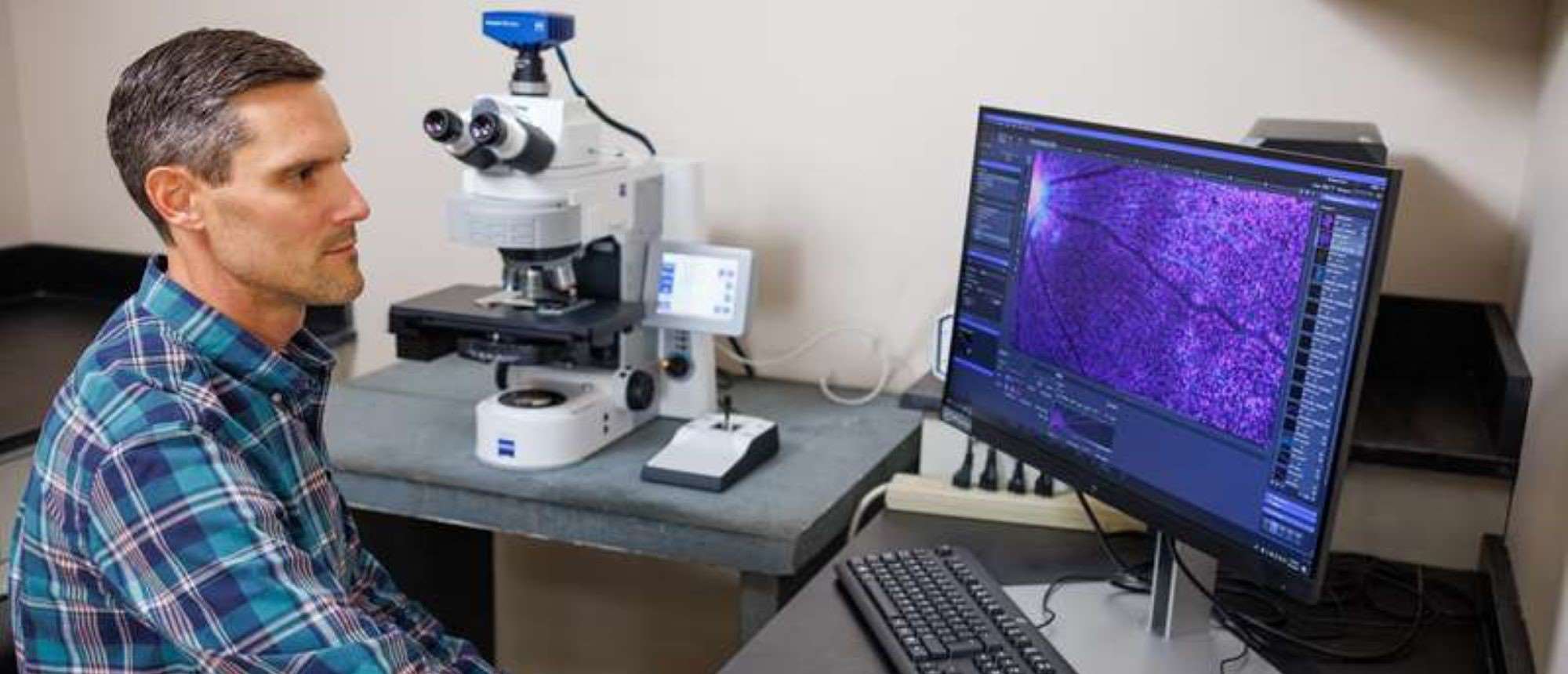

That’s exactly what Joel Miesfeld, PhD ‘15 wants to prevent. In his lab at the Medical College of Wisconsin, the assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, studies the development of these cells to better understand how to treat disease and to identify ways to help them regenerate after damage.

With a new R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Miesfeld will study the cells’ gene regulatory network and environment to understand what is essential for their genesis, differentiation, and survival.

“Without these cells, we can’t see,” he says. “The more we know about how the cells are made in a healthy way, the more we can keep these cells alive or help spur regeneration from the cells that are already in our eyes.”

Understanding How Retinal Ganglion Cells Regenerate and Survive

To enable us and other vertebrates to see, the retinal ganglion cells’ axons form the optic nerve, which connects the eye to the brain. Vision is so important to our survival that our bodies over-produce the number of retinal ganglion cells by 50 percent during early development.

“Then they go through this culling period,” Dr. Miesfeld says. “We want to know what makes some cells survive while others don’t.”

To find out, he and his team study zebrafish and mouse models, using genetic manipulation to test out key gene regulatory network transcription factors to better understand how they contribute to the cells’ growth and survival.

With the new grant, he will study these factors’ regulatory sequences, as well.

“All genes need to be activated in some way,” he says. “What's important about activation is that not only do you have to activate the right amount, but you have to activate it in the right place at the right time. Part of the grant is looking at specific DNA elements that are important for the activation of genes.”

Basic Research to Find a Better Treatment for Glaucoma

While his work is key to creating a basic understanding of these cells, it also could lead to new therapies. Diseases like glaucoma damage the optic nerve. If we better understood how retinal ganglion cells grow and develop, it might be possible to use neuropeptides to help the remaining cells survive and therefore stop vision degeneration.

“There’s also a link between the development of retinal ganglion cells and risk factor for glaucoma,” he says. “If you produce less retinal ganglion cells, glaucoma will lead to vision loss more quickly. If we can figure out what helps those cells survive, we might be able to slow that process.”

The ultimate goal is regeneration. There is currently no method of regenerating the optic nerve, but that doesn’t mean it’s not possible. Zebrafish, for example, can regenerate retinal ganglion cells.

“There are very smart people working on regeneration and they have found certain keys, but we're definitely not there yet,” Dr. Miesfeld says.

The Medical College of Wisconsin Offers a Collaborative Environment for Students

The new R01 grant will also support trainees in Dr. Miesfeld’s lab, allowing him to both “push forward basic science and train the next generation of scientists,” he says.

Dr. Miesfeld himself was once an MCW PhD student, training in the lab of Brian Link, PhD, professor of cell biology, neurobiology, and anatomy.

“He studied early retinal development and that’s how I got into this field,” Dr. Miesfeld says. “I love educating students here and this grant allows me to bring in even more students from Wisconsin and around the country.”

As a faculty member, he also appreciates MCW’s collaborative environment, which has helped spur his research.

“I get a lot of support from my colleagues, not only from within the Department of Ophthalmology, but from all departments across campus,” he says. “With that kind of environment, it’s obvious that the Medical College of Wisconsin cares about its people and the research we do.”